Teacher Who Was There Praises China’s Cultural Revolution

Mn. Daily, 11/4/75

By Martin J. Waters

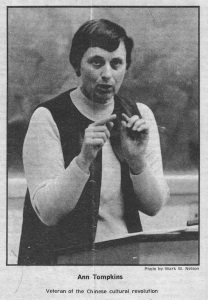

Ann Tompkins is one of just a handful of Americans who lived in the People’s Republic of China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution – “you could count them by tens,” she said.

And Tompkins was there to see the excitement from start to finish. She says she had more difficulty adapting to “culture shock” when she returned to the United States after four-and-a-half years than she did as a foreigner in Peking during one of the great societal upheavals of this century.

“Culture shock was a problem, but not as you might expect,” Tompkins said. “I had expected to have trouble when I went to China, but it was worse when I came back.” Tompkins said she found serious fault with many aspects of American culture. The American people need “some idea changes regarding greed and selfishness” before moving toward a true cultural revolution, she said.

Tompkins went to Peking in late 1965, when governmental relations between the United States and China were ice-cold. She stayed until 1970, serving as a teacher at the Peking Language Institute. She has returned twice – for 10 weeks during 1973 and for a month this year with a women’s China study group.

The tumult of the cultural revolution began early in 1966, several months after Tompkins arrived in Peking. For three years classes were suspended at the institute and at schools throughout China. Discussion of political issues filled the days and nights.

“It wearied you. You became tired of going to meetings. There were factions in our school and how to reconstruct the education to be offered was the debate,” she said Friday during a lecture in Anderson Hall.

Traveling the United States on a speaking tour, Tompkins is finding that “people are mixing up the question of revolution and cultural revolution in China.” She interprets the 1948 Communist takeover as a political revolution that was incomplete without a revolution of the culture.

Mai Tse-tung believed that, too. He said exploitative capitalist institutions had been abolished after 1948, according to Tompkins, but that bourgeois ideas persisted and that socio-economic classes still existed in China. Mao believed the cultural revolution would destroy those remnants of the “old society,” she said.

Education was probably the institution most drastically changed by the cultural revolution, with its “criticism and self-criticism,” she told an audience of about 100.”The change in education from 1949 to 1966 was real. Literacy was changed from 5 percent literate to 5 percent illiterate.”

A look at the backgrounds of youths admitted to the universities, however, showed there was still discrimination in favor of those whose parents were well-educated in the old society and against those whose backgrounds were of the working and peasant classes, Tompkins said.

The solution of the cultural revolution: abolish entrance examinations.

“Everyone works now for two years after high school.The the other workers pick those who’ll go to school, nd for the first time older people from the factories and farms who never had a chance to go to college are going,” Tompkins said.

Exams are now all “open book.” Instead of attempting to find out much the student has memorized, the exams ask “Can you figure out how to solve the problem?” she said.

“Nobody is to be failed. It’s the responsibility of the whole class to see that each one does well. If someone’s not learning it’s the fault of either the teaching or the administration” under the new Chinese system, Tompkins said.

“The idea is not to produce intellectuals who know how to do a little manual labor (by sending them to work for two years). The idea is never to let anyone lose touch with the workers,” she explained.

Economic incentives to prod workers toward increased productivity became a major issue in the cultural revolution, according to Tompkins. “Mao said if the people understand why more production is needed they will not need the cash bonuses.”

The thrust of the cultural revolution in all areas of Chinese society was to “reeducate” the people, eliminating remnants of the old society’s culture, she said.

After months of acrimonious debate the decision was made to give workers in each factory the option of continuing or abolishing cash bonuses. Tompkins said that she visited 32 factories during her 1973 trip, and found none with cash bonus systems. “I doubt now if any or very many have them” anywhere in China, she said.

The notion that the Chinese people are ill-informed about events around the world is false, Tompkins asserted. “There’s a great deal of information dissemination that doesn’t reach the radio or newspapers in China, so those looking from this country can’t see it.” However, she explained that mass media include local magazines, pamphlets and tape recordings played over public address systems and during public meetings.

In fact, “there is more discussion and more people are aware of the principles of policy toward foreign countries” in China than in the United States, Tompkins said.

Radio Peking broadcasts a 45-minute news program each morning, she said. “I knew more about the world listening to that news than I do in this country. Reporting all the rapes and murders across the country is something I can do without.”

Ann,

Mark Lee here–from the old days at Clear Water Ranch and then via correspondence when you were in China and I in India. I have a collection of your letters and wonder if you want them, perhaps if you are writing a book. Let me know and I can send them to you–after 50 years.

Mark

LikeLike

Whoa, sorry that we missed this somehow, Mark! Ann died two weeks ago – advanced Parkinson’s Disease – and she tried to be of use writing the book up to the end! Work on it is continuing.

We have boxes and boxes of letters that Ann wrote in China – overload already! Thank you for the offer and they might add to the story, but I think it would be too much for me (the writer) to handle. If you are reluctant to dispose of them, you could send them on to add to her archive (for which we have no home yet, but maybe). The address would be Media Freedom Foundation, P.O. Box 4477, Santa Rosa, CA 95402

Thank you! – Peace & solidarity, Susan Lamont

LikeLike